Program Notes

An Interview with Jerome Hiler and Nathaniel Dorsky

by Hannah Yang

Still from Marginalia (2015)

When I asked Jerome and Nathaniel if they might want to write something for the final screening of our nine-week program of their work, Nathaniel suggested I ask them some questions and talk about how watching their work had felt over Facetime. Jerome also provided program notes for the three films of his we are showing.

Many thanks to both Jerome and Nathaniel for their generosity and openness.

HY: Jerome, on the distribution pages of In The Stone House and New Shores on the Canyon website, it says that there are new revised versions available. I know for a lot of these films, you shot all of them and edited them later. I wonder if you could talk a bit about that and the idea of collecting this footage and re-assembling or re-editing it much later.

JH: Well, the revision was only concerned with New Shores, not with In The Stone House. I wanted them to be shown together, if possible, or in a certain succession. New Shores kind of meandered a bit and I wanted to sort of bring it more into a shape that I... I thought it should be a little more intense than the first film. In other words, the second film should be more intense. I just eliminated a lot of things that were unnecessary, and it has a more of a, as it were, polyvalent feel than the other one. In In The Stone House is very chronological and it’s actually unusual among my work because of that. The idea of going to New Shores also required a different mindset in the editing as well.

ND: Does Hannah know about the return at the end of New Shores?

JH: Yes, well that’s true too. We return to the world of In In The Stone House at the end of New Shores and it kind of brings it all together. Not only do we go back to the house, where we just sort of wanted to look at the house, but then Nathaniel had the nerve to knock on the door. And the people there — of course this is many, many years later — knew us from neighbors who talked about us. They welcomed us in and they were very excited. Many of our little things that were left there, they left exactly where we had left them. It was very unusual. We had no idea who we were, one another. They were very accommodating.

ND: They lent us the canoe you see at the end of New Shores.

JH: They allowed me to take the canoe out of their basement and put it in the lake. That was their suggestion, so it turned out to be an amazing thing. But in the film, not only do we go to the house, but we also jump back through the years and go back to the time of In In The Stone House to complete the seasonal journey of the first film. It has a sense of completion, at least at that time. The reason I did it was because — it had to do more with the fact that I knew this material existed, as it were, and it was very old. It was a sort of survivor of so many screenings in which I put together film shows for friends. Depending on what the mood of the time was I would prepare a complete new version of everything. The material from those years started to dwindle more and more as damage to the film occurred, and so I knew I had what were actually just fragments of things. I think it was around four in the morning one time when I realized, when people pass away, their friends might just go through their things and say, “Oh, look at this.” And, “we should put this together and make something.” And I thought, no, never, never, never. I’m the only person who could possibly put this together. I have to put it together. So that’s how Stone House came about. At the same time, Mark Webber in London invited me to show what he just called “an hour of footage.” And so I quickly put together two reels of film, and they became the...

ND: Template.

JH: Yeah, the template of Stone House and New Shores. But then I had to edit it, and that was a very difficult thing, because, trying to make something so far in the past present tense was not easy. And also engaging so, so much with the footage, I started to — it was almost psychologically challenging too. I could see myself and my world when I was young, and various good things and various mistakes I had made. And so it was both psychologically challenging, and also the challenge of making it come alive, something from the past come alive.

HY: We are obviously not as personally involved as you are, but seeing the younger version of you and then a few weeks later seeing a shot of you with white hair was shocking for us as well, to see that kind of chronological jump and progression. When you talk about making these films for people according to a certain mood, might that be related to your undistributed films that you list in the Illuminated Hours book? I see there are a few titles that, they’re not in distribution —

JH: Are they in the book?

HY: Gladly Given, Target Rock...

JH: Yeah, they exist. They exist. Gladly Given I will print. I showed it in New York, and I’ll gladly — gladly — print it. There are other things there that I’ve done. As far as the aging goes, I have to apologize for that too. Humans age more dramatically than any animal on the planet. But from the inside out, of course, it just seems all the same. It seems the way you see the world, as a 20-year-old, you’re still perceiving things exactly the same. I always thought as a young person that I would feel like an old person when I got old. I would see things differently. But actually, you don’t.

HY: I think it was a moment filled with the gravity of what we were seeing, the span of work that we’re seeing from both of you.

JH: I think almost all my work is about aging. It’s about time passing. Everything seems to go through some kind of thing. Even Words of Mercury, if you see it in a certain way, starts in the winter and comes to a kind of extremely, extremely vivid summer, and then suddenly it ends. It’s like a sudden death. There’s a little truck that goes off into the distance. I think almost any film I worked on has to do with the transformation that time brings about — almost everything. I don’t even do it consciously. I just look back now and I say, “Look at that, look at that.” It all connects. I don’t know what I do so much so that I’ll just go to a screening of my films and be shocked at themes that are there that I had not noticed before.

HY: Nathaniel, you also talked about a little shock when you see things in different orders, or films in different pairings. The screening that really worked for me was this combination of Colophon, August and After, Pastourelle, Intimations, Apricity. I think watching your films over these past nine weeks, what struck me is that I'll see a shot from week one and it'll resonate with a shot from week seven. For instance, there’s a shot, maybe the opening shot, of Hours for Jerome with the light seeping through the fog in the forest. It has the same quality of light as a shot in Threnody. It almost feels like a miracle to see something twice and recognize that it's resonating with each other, but I wonder if this is something that you are conscious of in your editing across multiple films?

ND: When one has these small retrospectives, one starts to see things all too clearly that are repeated — not in a negative way. You say, “Oh no, not another out-of-focus bush,” and then drive the audience crazy. But actually, you’re just reworking the same basic film. The film has something to do with your own being, your own metabolism, your own energy, your own sense of being awake. I think, by the way, I will tell my website team to include your suggestion of grouping on that page.

HY: It was really something. Multiple people told me it was the most impactful screening, and my professor was saying that it should be a singular film, like all the films together.

ND: Well, most of those films have some portraiture in them. Because my films, they approach humanness in two different ways. One is where the form itself has human qualities, and then the other is you see it, you actually see people. And it’s a big difference, because the first category is first person, and it’s like, I feel this, I see this. And then the second category is more theatrical. There’s actually a character. The whole screen actually goes thorugh a transition from being first person declaration to a third person depiction. It’s a threshold that I spent a lot of time trying to understand. Will this become too much third person theatrical, or is it too much first person? Can you get both of them to play in the same film? How do you transition from one to the other? All that kind of thing comes up. You know, the energy of those two directions. Does that make any sense?

HY: Yeah, the quality that you’re talking about is one of the things that resonated with me very strongly, after having viewed Threnody and also, Jerome, with your films. There were some moments where I felt almost terrified, as if the film were alive. Not that I was watching the film, but that the film was perhaps watching me. The film feels very alive in this way, that you’re thinking with the film, you’re watching with the film. Is there a recognition of this when you are shooting, or does the camera and the projection imbue the film with something else that is more than what you expected to see, and how much of this human quality do you also feel intuitively while shooting versus it only appearing in the editing of the work?

JH: Going back a little to what we were speaking of before, I think film viewers tend to think that everything was intentional. “Why did he put that? Why did he do that kind of thing?” I think, with me, most of the intentionality comes in the editing. It’s how you organize those things, and in a way, that’s why you end up repeating yourself, because you just are the same person. You go out and see the world the same way. You try your best to be different every time, but instead, you’re still yourself. The things that you are photographing, sometimes you almost feel like you have no power to resist. It’s just, this is where I look, this is where I go. We live in a very magical situation in life, where when we start working on something, it actually has its own life. There’s a dialogue between the two. It’s talking back to you. I’m not surprised you feel that the film looks at you, because I feel the same way. It seems that whatever we do, even if we’re not filmmakers, a kind of life starts to happen in the dialogue between the object and your mind, and you can be shocked and surprised and delighted at various messages and things that you see, and so forth and so on. Sometimes when you are working on the editing, you’ll see things in the imagery that you didn’t even know were there, or you didn’t realize something. So it's a very lively dialogue all the time. Then after it’s all over, you go to film shows, and you start to have those other epiphanies. “Oh, my God.” It goes on and on. There's one revelation happening all the time.

HY: Nathaniel, what do you think? Do you sense this when you’re shooting, or is it more in the assemblage of the images that you find this human quality?

ND: It’s a difficult question to answer. Well, there’s two things. I think that when you’re photographing a person, your duty is to be selfless and let them and let their qualities connect to the audience. But when you don’t have a character, then the film itself is the character. Just like doing a portrait of somebody, in a way, you're doing a portrait of a film. The way energy switches from something more intense to less intense. Rather than just graphics or description, it’s more like trying to awaken the energy of what it feels like to be alive.

HY: And this is something that you navigate through for long periods of time. Is that energy more about what you see in that moment or is that something that you can re-access when you’re editing, or something that you find in the images themselves?

ND: There are various things. I once asked Stan Brakhage, “How do you edit? Your films look, feel like they’re coming right out of the camera. How do you edit to get that feeling?” And he said, “I edit in the same spirit that I shot.” He obeyed the rules and so forth, so to speak. In a way there’s that kind of thing. Let’s say you’ve collected this footage like Hours for Jerome. That was almost three years of collecting where other films will be shot in two afternoons. So it’s always different. But when you start to make a film, at least with me, I found the thing to do is find what the first shot is. Otherwise, you’re completely lost. You got all this footage, and you go, oh, I’m going to start with that. I’m going to invite people in. It’s like a doormat. Come into this film, enter this film. Then once they’ve entered, it’s sort of like being a host to a guest. You offer them something. Or you take their coat, in a sense. You don’t give them water before they sit down. It’s the same basic logic of being a host, a generous host, and that you want to take the audience on a trip, and that it’s important that they get to trust you, that you’re not going to get too weird suddenly for the sake of being weird, but there's a little more trust, and then you build from there. Then from that point on, as you feel the energy of where you are in the edit, you feel, oh, let’s relax that, or let's intensify that a little more before I relax that.

The working with the polyvalence — it took a long, long time. In my film Triste, which I think you showed, it took me something like three years to edit. Because I was trying to figure out how this open form would work. You have to achieve two things at the same time. The film is going forward, and at the same time, it has to be present. In other words, it has to be a new presentation of the present moment.

HY: I wanted to ask you was about that sense of temporality. In a typical film, there’s a time within the film, where it goes from one shot to another, but within your films, there’s no time that connects those two shots, but it’s rather a kind of temporality that exists between myself and the film.

ND: Well, it’s interesting that film creates its own sense of time. Probably not unlike music. The idea, at least in the way I edit is — for instance, in normal filmmaking, each shot takes you further and further into the fantasy of what the narrative is. And in this case, I’m always restating the present moment. So it’s more like crossing a stream with rocks in it, and you’re stepping on this rock and that rock and that rock. But as you go, as you step on each rock, the present is evoked. It’s not a shot that's referring back to the shot before itself as such. But yet it is. And I think it’s a little bit like the human mind. At least I noticed in myself, there’s a slow part of my mind and a very fast part of my mind, just like the way I dream. You could fall asleep for a few seconds in a movie, but the dream is much more complex than your entire movie, and it’s only three seconds long. So that’s the fast part of your mind, which comes from not having to translate your meaning into language to yourself. You don’t have to re-speak it. I don’t know if you've noticed the times when you can realize you’re wondering, is this a good shot or not?, but you actually know it's a good shot or you know it isn’t. You actually know it, but you’re starting to bring it into the world of language: “Is this a good shot?” That's kind of the slow part of mind. So what I’m trying to do, in a way, is activate and address the fast part of mind, you know? That’s what intrigued me a lot about working on film.

HY: Yeah. When I’m watching the films, what I really don’t want to do is put language to it and think about it and narrativize a shot, like I really just want to be inside the image. And I think those are the moments when I feel most moved. There’s a shot in (maybe) Song and Solitude, or two shots, where I can't remember what the first shot is, but maybe it’s water on glass or something, and then it cuts to a man’s shoulder, his coat, as he moves by. I think, because I was so inside the first shot, that the cut is really what’s moving me.

ND: As I said, I think it’s like the fast part of mind, the part that doesn’t have to verbalize something to yourself. As I’ve gotten older, you get better. The more films you work on, the more your mind is intelligent about decision making, not the spoken, not the way you speak to yourself, as in: is this working, but the actual essence or meaning of what’s happening is more available to you.

HY: Jerome, after I watch your films, my friends and I will often talk about how when we walk home, our eyes seem to trace things or see things as in your films. I feel like your camera is very intuitive in that way, that you’re tracing a line or a fence or scaling a pattern. And then, Nathaniel, I have almost no sense of what your camera is doing. I don’t feel that it’s moving sometimes, but it is.

JH: I think, of course, it’s one of the big differences between Nathaniel and myself. We often note that I look through my left eye when I’m photographing, he looks through his right eye. And the whole world of the left eye and the right eye are very different. We cling to our differences because we have so much that in life we enjoy together, and we try not to be the same filmmaker. I just have more of a, maybe a dance-like thing. I’m there and I’m moving around, that sort of thing. I’m more dancing with the environment than contemplating the environment. I have always marveled at how a film re-sets the way you see the world afterward. A film can direct your attention in the subliminal ways and have you continuing it into your own life.

ND: Jerome also comes to filmmaking as a painter. I came from it more as a poet. I remember I would be finishing a film, and Jerry would say, “Let me see the colors.” This is not that kind of movie. Of course, the colors are very important, but it’s not the main thing, where I think Jerry's functioning more as a painter, as a visual presenter, and I think I’m trying a little bit more, maybe, to touch the heart of the audience. The things you were talking about when you get very moved by a juxtaposition between two things, I’m sort of interested in touching the heart right here (points at this chest). Most of the decision making is based on this [touches heart] and not the verbal part, “is this good or not?” Because you’re always unsure. But if your truth is being activated, then you have some confidence that the film is working and that it will work for an audience also.

HY: Color seems to be some kind of arranging or compositional principle, but also textures — transparencies, opacities, granularity, and also planes. I’ve been able to see your films from a wide range of vantage points, and what always strikes me when I’m sitting further back is that you’re not only working with images within the film, but also somehow it transcends the screen. You’re working with planes that shift across the screen in different ways.

ND: Well, one thing I learned a lot from Jerome is... I noticed in Jerome, before he even finished a film, his footage activated the screen, so the screen itself became an active thing. And I learned a lot from that. That’s one of the things. On the cut, two things have to work: the composition, the weight or balance, has to really be right, and also the color. The colors are more like your emotions, your moods. Like a composer might change his key signature from one thing to another to present different aspects of a mood. Filmmaking is a little more like that.

HY: Jerome, I also know that you're doing these superimpositions. I know that you do in-camera editing as well. You mentioned dance, and I wonder what role improvisation and spontaneity has in your work.

JH: A principal role. I would say the principal role is spontaneity. I am always trusting. I only go forth with a sense of trust that what I am going to see, encounter, what will attract my eye, and so forth, will be of significance or not. I just like to interrelate with things. I’ll also have to ask, what is this film about? I don’t ever say I’m going to be making a film — I might want to make a film about something — but instead, it’s going forward with trust that — it’s just like your life. You look back and you’re puzzled at all the different ways that things have happened in your life that were beyond anything that you had planned for. So I go forth with that when I go out and engage. And if something doesn’t fit in, something doesn’t fit in, and other times it leads someplace.

Now, as far as superimpositions go, it’s very difficult, in a way, because you try to remember what is on a roll. Sometimes I’ll take notes and say, this is happening. But then there are sometimes four layers. They don’t all look like four layers and so forth, but there are four layers and at that point, this takes a while. It’s not something that happens all in one day. It happens over time, and you forget what else is down there. You have to think in terms of introducing something to something else that you don’t quite know what it is, either. And that’s part of it. It’s part of how our minds work, or my mind works. Sometimes I will have a moment between two thoughts, and I will almost imagine I hear some kind of voice on a radio somewhere, a pilot asking to land somewhere or something like that. It’s the kind of chatter that you don't pay any attention to. And once in a while you do pay attention. You say, “Where is that coming from?” Sometimes things come into my mind that are so — have nothing to do with me at all, and that is the sort of spirit I also have with superimpositions, that I have to just know how to do it. And then later on, I’ll see what’s there, and it will be good or not. But the thing is, it's so persuasive once it’s there, once it's successful. Then, as I say, the viewer might say, “Oh, he planned it so beautifully.” This happened, and you know, all these things happen, but I don’t know. It comes just with practice to how to shoot in a way that allows other things to happen. And then you’re really open to surprise.

ND: Can I say one thing about the color? The color — which is equivalent to the emotions —if the color isn't right on a cut, if it isn’t articulate in some way, the same way a key change in music would be articulate, then nothing can make the shot work. At least my perception is, the most primal thing is the actual color. It's before shape or composition. The initial ding is a color thing and so the color has to be interesting or make some emotional sense. Not the sense of describing where you are — it’s unspeakable at best, an unspeakable sense that it’s right because it is right.

HY: This is a question that I think I often struggle with, and watching your films, I feel like maybe I’ve found more of an answer, but it troubles me all the time. What is cinema for? Why am I here in this room watching this film instead of going out and observing these things in the world, rather than through a film?

JH: First of all, I'm so happy you asked that, because I often think the same thing myself. What is it that we’re doing? When I say we, all of us, together — the audience, the people making the films, that kind of thing — what are we doing? Maybe we don’t have to get to an answer. Maybe we can just enjoy the question. Just asking the question is the important thing. Otherwise, if we just talk about, “how did you get that shot,” and “how did this happen,” it becomes a hobby, a hobby club. But this is something that goes beyond it, because it’s about our minds and how we see and feel. It’s sort of a reflective media, that you step back and the dark theater is like a skull. And there’s your eye up there on the screen, and you're looking out at the world, and you're sharing some kind of being with everyone. I think it’s a very spiritual thing. It’s a form of meditation where you just step back, get quiet, sit down, and you look and contemplate things. And then you start thinking in some way about how it affects your life and so forth. So that’s what I think — I hope — what I feel as a filmmaker, what we’re doing. I also feel like it's such a serious responsibility to be a filmmaker, to respect that situation, to respect the audience, to respect the people who come. Because nobody's in charge of this thing. Not even the filmmaker is in charge. And you just have to respect all the property so that you’re not abusing the viewer, and things like that. And you have to respect the power of the situation properly. Your film is all that is happening in this dark room. That isn't an ego trip. It's a responsibility.

ND: People benefit from being taken out of their own world. In my case, I want to take them out of their own world, but present my most intimate and strongest feelings about things. But it would be more like, just by touching their elbow a little, like, “look at that,” rather than making a statement.

JH: It's funny, when i's time to show your film at a show, what is there to say? The film is the message and the reason we have art is to "say" what can't be said in words. I might try to set a tone, but nothing more. The pleasure of speaking and writing comes afterwards. There we try to share our minds through the prism of the film.

ND: It’s like an interview of an athlete. “What were you thinking when you caught that ball?”

HY: Yeah. Thank you for indulging me and answering my questions. It was so special to see these films over a nine-week span, because I think it really structured my entire fall. And whatever I read or watched or thought about, it always came back to these films. So I want to thank you for that. It was a real gift.

JH: We’re all a recipient of a gift. You know, all of us. So let’s enjoy it.

HY: One more thing I wanted to ask — what are you doing with the fades and the fade to blacks?

JH: It’s a big question of the thing about black, darkness. I think it’s something we both have in our films. And there are so many ways you could discuss it, but basically the idea is, we’re dealing with vision and light. Inevitably you would start to become just as fascinated with the lack of it, the lack of that thing. I had done this lecture called Cinema Before 1300 which was about medieval glass, and that dealt a lot with light emerging from darkness, and also how important darkness is to filmmaking, filmmakers, and the film viewer. You need that darkness right in your theater. It’s the arena that allows a film to happen. So you just bring that also into the film itself. Light emerging from darkness. You feel the power of that darkness. It’s so rich and pregnant and always giving birth, to light and the images of light — images of light giving birth from that darkness. It’s all part of the whole picture of what film is. It’s no surprise that you would want to include that.

ND: Also, you know what, Jerry, the handmade fades are more in the spirit of the handheld camera. Where a lamp fade, which is very mechanical thing, feels slightly other than the camera movement, camera being held in the hand.

HY: Yeah. I used to say my favorite part of a film is right before it starts, because it’s kind of pregnant with this possibility, it’s not just a lack of light. The black is totally different than the gray that appears when the projector is off. It’s something entirely different.

JH: It’s also becoming rarer and rarer in our lives to have darkness. These are the Light AGes, where there’s constant information going on all the time. Everyone is always afraid and at night, every back alley has to have more lighting. Animals or insects are dying off. No more fireflies and things like that, because of the amount of light we have. So it’s essential that we experience darkness. We’re formed by the fact that we live on a ball that goes from light to dark and light to dark. And that’s where we come from, and it’s just very important. Darkness is very important.

HY: It seems like another kind of answer to, what is cinema for? It’s for these moments of darkness where we are able to sit in the theater and experience it. And also, the slowness of your films too, because the expectation now is just brighter, faster, and your films are slowing it down to 18 frames per second.

ND: Yeah, the slower frame rate is very, very important, at least to me. It’s more like a purring cat, rather than, I don’t know, a machine gun. Sometimes the 24 frames a second sounds like it’s trying so hard, but it's going at that speed for the audio presentation of the film. And since there’s no sound in the films, there’s no obligation to be at 24 frames, which is kind of a sound medium. It’s more solid. The other is more tentative.

This interview has been edited for the sake of clarity

Jerome’s Notes on his films:

Still from Ruling Star (2019)

MARGINALIA

In MARGINALIA, I allowed myself the indulgence of being gloomy as I looked upon our world. Simply allowing the mood. The idea of being marginal as the world darkens. I felt the film to be like scribbled notes beyond the borders of society. I wonder how youngsters cope with their entry into this world. Some of them tell me they don’t understand cursive writing and I need to use block letters if I write to them. I see the role of parents as they pass along skills. I remember the trauma of learning to write letters myself and the repetitious attempts to form the proper shapes. But, here comes my revenge as I scratch undulations of sine-waves and the cursive lines become pure light, waves of joy.

RULING STAR

The older I get, the more basic my concerns and interests are. RULING STAR is an homage to the nearby star that has given us life. In fact, without it, consciousness wouldn’t exist. As far as anyone knows, we haven’t heard of anyone else “out there”. The film starts with a little overture as we visit a suburban faux-Egyptian temple and allow Pharaoh Akhenaten to be our votive. Wasn’t it he who sensed a vast interconnectedness among all the forms of existence? With the the rays of this “Sun” as guide, I wander around the still-baffling state of California as a stranger in a strange land.

CARELESS PASSAGE

Wandering through the ordinary sights of day and night. How, in this vast cosmos, did all this happen? We live in a world of constant transformations. Somehow, aeons ago, consciousness came about. I’m often drawn to think of the earliest stages of life when we were swimming blindly in water. How was it possible to develop that bubble-like appendage to our brains that allowed the great miracle of sight? What a revolution in that infinite cosmos for consciousness to join with sight. (All this taking place among bubbles near a warm shore). Was this event some kind of mandate from the Universe so that it might know itself? Are we tools in that quest? How do these thoughts fit into the parade of ongoing distractions that make up daily life? CARELESS PASSAGE will answer none of these questions. Its purpose is to muse and swim among migrant sights seen by the transforming eye of a camera.

To Feel Again

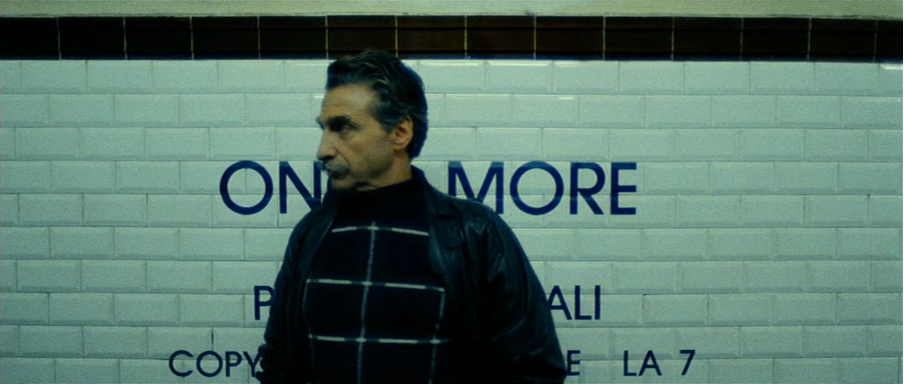

On Paul Vecchiali's One More (Encore)

by Oscar Pederson

Written for the series Paul Vecchiali and Diagonale.

Still from Encore (1988)

During the pandemic and until his passing in 2023, Paul Vecchiali posted capsule reviews of the films he saw on Facebook. He would share off-the-cuff impressions almost daily, and it was impossible not to be charmed by them. Often, you would even learn something from them. A few examples:

September 21, 2020, The Woman in the Rumor (Kenji Mizoguchi, 1954): “A tragedy treated with a touch (!) of lightness, and therefore with real depth. A Mizoguchi that seems to be frolicking about but gradually takes hold of you. The greatness of the film lies in this ‘little by little.’”

February 5, 2021, The Fear (Viktor Tourjansky, 1936): “A pure marvel. Simplicity and finesse in the adaptation of a great novel. Morlay and Vanel are magnificent.”

July 13, 2022, Made in Italy (James D’Arcy, 2020): “I don't care if people call me naïve: I consider MADE IN ITALY one of the finest films of 2020, and perhaps even beyond that! James d'Arcy wrote it, and it’s his first film! Liam Neeson deserves an Oscar. And the supporting cast does not disappoint.”

September 11, 2022, The Breaking Point (Michael Curtiz, 1950): “More powerful than Ford? Equal to Mizoguchi? When I see BREAKING POINT, I tend to think so. Curtiz is not content with merely making movies; he lives with his characters, embraces them, and doesn't judge them. This film is a miracle.”

An interest in narrative structures, a fascination with well thought-out characters, a love for the actors who made characters come alive, and an admiration for the filmmakers who churned out a cinema both popular and marginal. Those are the values Vecchiali often cherished in other people’s work. But are they not also the values we find in his own work? Take Once More (1988), for example. Drawing on traits of the melodrama and the musical genre, Vecchiali confronts the AIDS crisis of the 1980s in a manner that is at once direct and reflexive. It is structurally organized around ten moments that occur on the same date across a decade (October 15, 1978-87), creating vibrations of both linear and circular movements. Once more, once more, we progress and return. At the center of the film is Jean-Louis Rolland’s character, Louis. It is his film. It is his actions that the camera and our eyes follow. And yet, the film also belongs to all those said to be “inappropriate,” all the outcasts that come along Louis’s way. The film starts with a promise to the spectator: feelings will be involved. Feelings are difficult to arouse; they demand attentiveness and serious care – from the filmmaker and us. Let’s not forget Sam Fuller’s statement in Jean-Luc Godard’s Pierrot le Fou (1965): “Film is like a battleground. There's love, hate, action, violence, death... in one word: emotion.” Vecchiali does not sell us emotions, he offers them to us. Vecchiali’s emotions are not only expressed through the characters but through the entirety of cinema, this heterogeneous medium of time, movement, stillness, silence, sound, music, space, sensations, people, and objects. Vecchiali’s cinema puts faith in its audience and the love stories on screen.

Vecchiali always reminds us that acting comprises the dual existence of an actor and a character. The camera cannot distinguish between these two. All it sees is a body. It is, therefore, up to the filmmaker to create a dividing line, to mark the point where the actor ends, and the character begins. For Vecchiali, however, it’s about allowing actors and characters to emerge equally, side by side, without hierarchy. It is through Vecchiali’s structure and formalism that we see not only the contours of Louis emerge but also Jean-Louis Rolland. Amidst the well-choreographed dance between the camera and Louis, amidst the incredible sets of blue bedrooms, underground gay bars, and hospital rooms, it is as if a live performance takes place from which Rolland’s melancholic intensity shines. We see the co-existence of character and actor and their respective temporality: The character’s predetermined destiny as it is shaped by fiction and the actor’s documentary execution of it. In this way, Once More forms a spiritual kinship with some of cinema’s most fascinating characters: Gena Rowland’s Sarah Lawson in Love Streams (1984), the entire cast of Jacques Rivette’s Out 1 (1971), and Maria Gonçalves, whose character Vera in Rita Azevedo Gomes’s Fragile as the World (2001) gives off a fragile warmth that shimmers transparently in the film's black and white images. In all these films, the fictional space is enriched by a documentary experience from which genuine emotion emerges. So, once more, once more, let’s feel once more.

Oscar Pederson has also written about the Diagonale films in his essay "Streets of Parisian Fiction: The Adventures of '80s Cinema" for Sabzian.

Alaya

Written for The Devotional Cinema of Nathaniel Dorsky and Jerome Hiler at Doc Films, playing every Sunday at 8pm.

Still from Alaya (1976-87).

Birthed from darkness, the first image in Nathaniel Dorsky’s Alaya is shadowed dunes. Almost indiscernible, the repeated mounds of sand only manifest themselves on film through the light refracted on their western slopes. As the dunes emerge from a deep black, their structure is collapsed through a cut to a green field of sand – shot from the same cartographic position. From this new shot, the depth elicited by the reflected light of the previous shot from the dunes is flattened into a plane. This plane metamorphosizes as air directs its millions of elements every which way. Though generally a uniform hue of green unites the projected image — the abnormal color likely resulting from being shot on an outdated film stock — the screen glistens as light catches individual grains at the perfect moment so that the brilliance of the reflected light is etched into the film, each for only a fraction of a second. Alaya draws upon a fascination with grain and its homonymous associations, which Dorsky began exploring in Pneuma, focusing on grain patterns in expired film stock. It continues a granular trajectory, focusing on sand grains.

The first shot of Alaya discerns the grains of sand from the decaying silver halide crystals in Pneuma through the element of depth within the filmic image. This space, present in photographed film, is a central element to Alaya’s elucidating nature. The cartographic camera position present in much of Alaya’s assemblage emphasizes the space. Given that the direction of the gaze aligns with the pull of gravity, the space between the grains of sand and the grains of silver on the soon-to-be-exposed film strip in the camera feels as if it is in a charged state, yet the pull reifies the presence of the distance between the apparatus and its subject. But this space is not a vacuous chasm separating photographer and photographed, rather it is a plastic atmosphere through which transmissions of light travel. Scale shifts in the work as almost microscopic shots in which one can discern a singular grain from another permit a greater diversity of reflected light as the vibrant grains take on a crystalline relationship with the light and color that they reflect. Shots distant from the camera — of Death Valley’s rolling dunes — harmonize the grains into forms subject to the direction of the winds, yet all are intrinsically tied to the essence of light and its being as the great bridge between photographer and photographed.

The organic plasticity of this medium bonding object to film strip feels at odds with the regimented and orthogonal apparatus. It is almost a violent harnessing of the photographed’s essence at every point. The camera’s eye takes in light, shaping it so that the illuminated plane is condensed through a circular lens and trimmed to fit a 4:3 frame. Yet Alaya displays a harmony between the organic and orthogonal. Near the beginning of the film, a shot appears; regimented slipfaces draw parallel lines across the screen. Atop this dune, the wind blows downwards. This amorphous cloud of atmospheric trajectory is manifested visually through its carrying of sand grains giving it a tangible form. This harmony evokes a coherence between the static, almost mathematical, lines and the plastic atmosphere washing over the ordered dune. At its core, Alaya illuminates the intrinsic lighted quality of film and its modes of mediation; a cosmological work through which grains shimmer as stars in the distant sky.

Text and programming by Jackson Zaro.

Nature and the Camera in Vadim Kostrov's Films

Written for Manifested Time: Vadim Kostrov at Doc Films

Oct 11-13

Still from Normandie.

In Vadim Kostrov’s first seasonal film, Summer, the camera is frequently in motion, making the filmmaker felt sharply as a presence in nearly every scene. The ways in which the camera attempts to trace a subject, shape, or path of movement conveys the earnestness of a filmmaker early in his career. Two years later, in the stillness of Fall, a technical and cinematic maturity that was hinted at in the warm freeness of Summer is reached. The playful nature of young Vadim in the first movie has quieted into a reflective adolescence that colors every shot.

In Fall, the camera takes on a different relation to what it captures. Zooms and pans are carefully paced and camera movement is incremental, staying close to its subject. Rather than imposing a searching or controlling gaze on the nature surrounding it, the camera stills and submits to the moment, allowing nature to reveal its splendor. This leads to sublime moments: light shifts from foreground to background, illuminating first a patch of grass, then a building front in the distance; a long, still shot above Nizhny Tagil at sunset captures the increasing density of orange and reds as the sky darkens. It is nature that molds shots like these, not simply the will of the filmmaker. A collaboration occurs: the camera needs to be placed in front of nature — and our eyes need to be open to it — for us to see the radical transformations that occur in the everyday.

These transformations are ones that seem to define Vadim’s life in Fall, amidst a routine life in a routine neighborhood. It’s a familiar concept: in childhood, shadows take on shapes and light is something to play with. We interact with nature on a more active level. Kostrov pushes this idea further in Normandie: we mix with our environment, our being is shaped by it. The film in moments abandons the central couple to take in the sheer size of the cliffs and ocean. Their words are barely distinguishable over the sound of the sea and wind (a logic that also drives the faintness of the subtitles). Although Kostrov often speaks about what his films do for the people involved in making them (his actors — often family and friends — and himself), the transformative power of his images for the audience must not be understated. Sitting with a still shot of the glimmering sea for an extended amount of time does something to us, and this is the belief from which Kostrov operates. If cinema is experienced as real (or something akin to it), the images we see have the effect they would in life, or more. Kostrov creates an intense relationship between ourselves and the world in the theater.

In the collection of short films (Three Days Before Spring, Glimmering, Waning, and Dans le Sacré-Cœur) the camera shakes off its stillness and takes on a more mobile, active character. Kostrov often describes the camera as an extension of himself; he moves and captures on instinct. This instinct is coupled with decisions about time — when to meditate, when to move on — and perception. The subjects in the shorts are both realistically photographed and abstracted. The leaves of the trees in Kostrov’s backyard gain significance not simply for being leaves, but for their swaying movement and the lights and shadows that can be extracted out of their image. Kostrov blurs their texture by pulling out of focus, turning fixed, defined shapes into an amorphous, affectively murky visual field of dark greens, yellows, browns, and blacks. The camera is interested less in the fact of the object and more in our feeling of its essence through an altered perception of it, an essence which is made visible only through the camera. Out of these small scenes of abstraction, a universal fabric appears, in which everything has the same internal rhythm. The skin of someone's arm, the muted glimmer scattered across glass, the gentle lifting of tarp across a surface all become united instances of the poetic, lifted from the mundane.

These portraits of nature made visible through the filmmaker’s camera are immersive and meditative. They create a totalizing cinematic space and time in which nothing seems more present than the image in front of us, and we become aware of our awareness, our being in the world. Out of the various scenes captured from Nizhny Tagil in Fall, the cliffs of Normandie, and the everyday Paris in his more recent works, Kostrov creates a space for us to regain ourselves in. It is perhaps a gift to be conscious of this world. So often our lives rush by and we increasingly miss the incredible moments that exist all around us — a passing cloud, a particularly beautiful sunset — but in Kostrov’s films, these moments constitute the whole. We mix with nature and the world through Kostrov’s lensing of them; these images hold our past, present, and, as we are transformed by experiencing them, maybe even our future.

Still from Fall.

Text and programming by Hannah Yang.

This presentation was made possible by the support of the UChicago Department of Cinema and Media Studies, the Center for East European and Russian/Eurasian Studies, the Film Studies Center, and the Parrhesia Program.